Making a firewall using eBPFs and cgroups

eBPFs are fun. They present an easy way to insert pieces of code in the kernel which are compiled to opcodes which are guaranteed to not crash it: The instructions allowed are limited, backward jumps are not allowed (so no indefinite looping!) and you can’t dereference pointers, but can instead do checked reads from pointers which can fail without panicking the entire system. You can attach an eBPF to thousands of hooks in the Linux kernel - uprobes, kprobes, tracepoints, even things like page faults. They have a lot of exciting features and are very actively developed on - you can see a list of features that are supported per kernel version at https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/docs/kernel-versions.md.

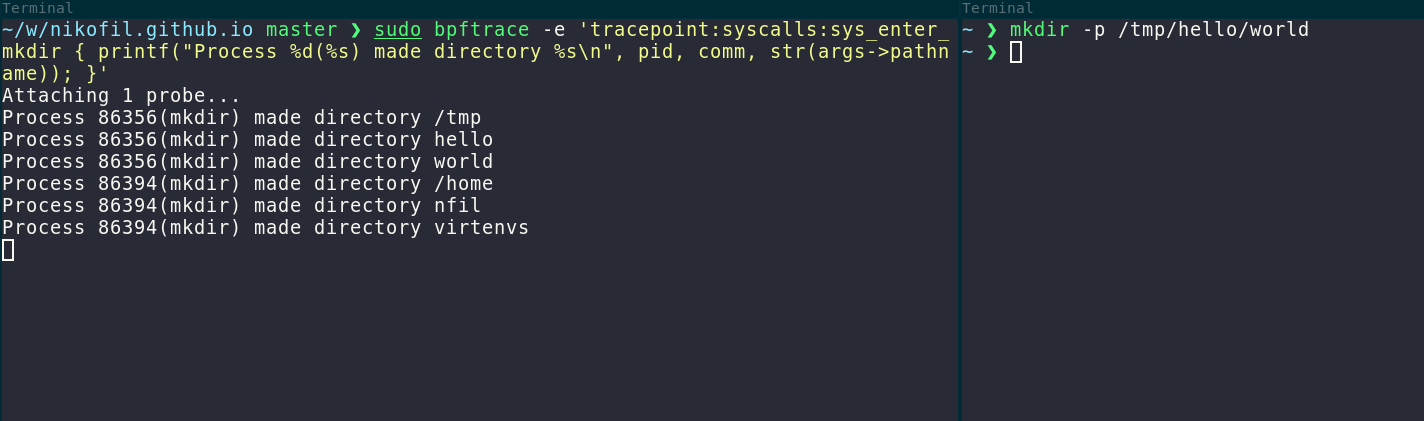

They also have great tooling available - you don’t even have to write any code for some basic usages. For example, you might want to see all instances of mkdir syscalls, which you can do with an one-liner:

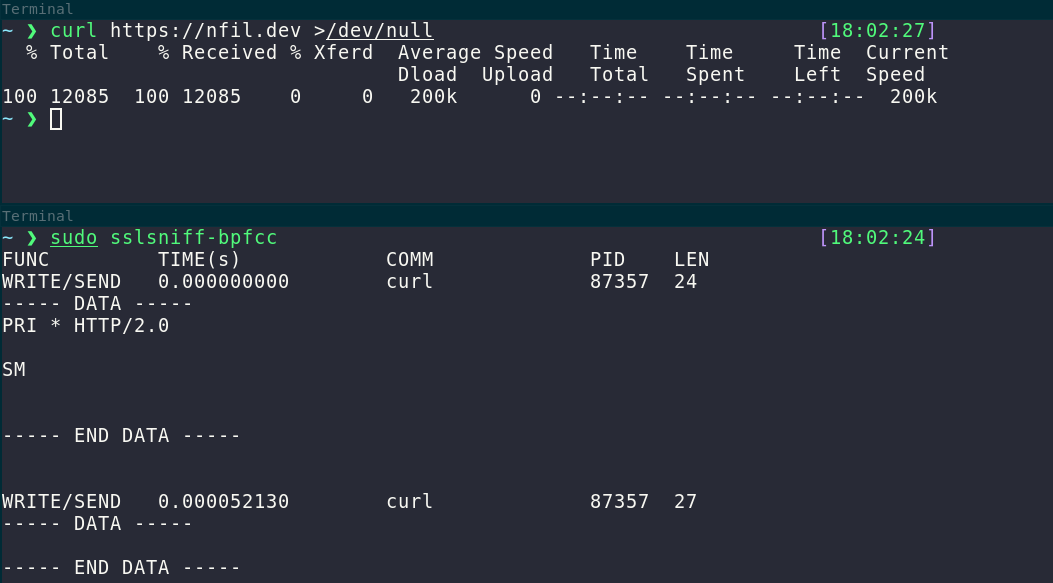

Or you see a process making TLS connections and wonder what it’s sending? That’s easy too, you can just hook the appropriate functions in OpenSSL that do the encrypting using sslsniff.

Looks like Github pages is using HTTP/2. :) Brendan Gregg famously has many articles on this suite of tools.

There are several articles about how eBPFs are taking over all things firewall in Linux in future versions. They’re going to be a replacement for the backend of the iptables command as they are a lot more flexible and also faster: instead of having a series of rules that might match a packet or not a la iptables, you can instead write code that determines whether a packet is accepted, dropped or edited! Some of these hooks run as soon as an incoming packet is placed on the NIC and before further processing occurs, saving precious cycles, and can even run on specialized hardware.

Even for this usecase, there are several hook points to attach your program to and then decide a packet’s fate. You can use the modern XDP (eXpress Data Path) hook which is triggered as soon as the packet arrives, before the kernel even allocates memory to copy it from the NIC. At the moment this only supports ingress traffic which is not what I wanted to work with. Another option is to use the largely unknown Linux traffic control (tc) subsystem’s hook points which supports both ingress and egress and many options for what to do with the packet: drop, redirect to another interface, edit or allow it. This is a great option but wasn’t supported on my CentOS system at the time. So I settled for the third option: cgroup hooks.

Now, cgroups are normally used to restrict how much of a resource a set of processes can access, such as CPU cycles or RAM. This way you can have multiple Docker containers without one taking up the entire system’s resources, and you can edit these limits on the fly. But it also provides a simple egress and ingress hook for deciding whether a packet is allowed. Attach a function to them, return 1 for allow and 0 for drop. Easy! Time to write some actual code.

First of all, we need to be able to compile our eBPFs using Clang. To install the requirements, you can run the following on CentOS 8: yum install -y clang llvm go or on Ubuntu: apt install -y clang llvm golang. The cgroup2 FS must also be mounted, which by default is mounted on /sys/fs/cgroup/unified. If it’s not, you can mount it with sudo mkdir /mnt/cgroup2 && sudo mount -t cgroup2 none /mnt/cgroup2. Now then, to the actual code part.

There is a useful header file called bpf_helpers.h which you can get from the Linux source tree: https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v5.4/tools/testing/selftests/bpf/bpf_helpers.h. This includes many macro definitions for calling eBPF functions, such as for copying stuff from kernel memory to BPF memory or accessing hooked method arguments, which will come handy.

The bare minimum code to block all packets and be certain that your computer is safe from the bad people on the internet is:

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <netinet/ip.h>

#include "bpf_helpers.h"

#define __section(NAME) \

__attribute__((section(NAME), used))

/* Ingress hook - handle incoming packets */

__section("cgroup_skb/ingress")

int ingress(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

return false;

}

/* Egress hook - handle outgoing packets */

__section("cgroup_skb/egress")

int egress(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

return false;

}

char __license[] __section("license") = "GPL";

You can compile this with clang -O2 -emit-llvm -c bpf.c -o - | llc -march=bpf -filetype=obj -o bpf.o to get an ELF file for target architecture BPF.

Let’s see what this ELF file contains.

$ readelf -S bpf.o

There are 12 section headers, starting at offset 0x610:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000568

00000000000000a7 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[ 2] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 4

[ 3] cgroup_skb/ingres PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

0000000000000158 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 8

[ 4] .relcgroup_skb/in REL 0000000000000000 000004e8

0000000000000030 0000000000000010 11 3 8

[ 5] cgroup_skb/egress PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000198

0000000000000158 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 8

[ 6] .relcgroup_skb/eg REL 0000000000000000 00000518

0000000000000030 0000000000000010 11 5 8

[ 7] maps PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000002f0

0000000000000038 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 4

[ 8] license PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000328

0000000000000004 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 9] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000330

0000000000000050 0000000000000000 A 0 0 8

[10] .rel.eh_frame REL 0000000000000000 00000548

0000000000000020 0000000000000010 11 9 8

[11] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 00000380

0000000000000168 0000000000000018 1 10 8

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

p (processor specific)

$ readelf -s bpf.o

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 15 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS bpf.c

2: 00000000000000a0 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 3 LBB0_3

3: 0000000000000100 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 3 LBB0_6

4: 0000000000000138 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 3 LBB0_7

5: 00000000000000a0 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 5 LBB1_3

6: 00000000000000e0 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 5 LBB1_6

7: 0000000000000138 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 5 LBB1_7

8: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 3

9: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 5

10: 0000000000000000 4 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 8 __license

11: 000000000000001c 28 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 7 blocked_map

12: 0000000000000000 344 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 5 egress

13: 0000000000000000 28 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 7 flows_map

14: 0000000000000000 344 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 3 ingress

You can see the __section macro did its job: The functions we defined in the C code were placed in their own sections, and there is also a symbol for each. The names of the sections are important: cgroup_skb/{e,in}gress is a convention that refers to the place in the kernel where this eBPF program will be hooked to. The symbol name is also important for later referring to our programs. “SKB” stands for socket buffer (also known as sk_buff) which is how a packet is stored in the kernel. As you might see in the C code, it is also the type of the argument our programs will receive when executed. The socket buffer contains everything we need to determine the packet’s fate, although currently we use none of that and just trash all packets without discrimination.

You can’t just run this, of course, as it has no entry point. You have to load it! This normally happens with the bpf system call which handles all things that we want to ask the Linux kernel to do with eBPFs, such as loading a program or creating a map to communicate with userspace, which we’ll do later. The Cilium eBPF library for Go helpfully takes care of the low-level stuff for us. The following Go program takes our BPF binary file and loads it into the kernel.

First the necessary imports:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"path/filepath"

"github.com/cilium/ebpf"

"github.com/cilium/ebpf/link"

"golang.org/x/sys/unix"

)

We define all the constants in the start of the program to keep it clean. These include the path for the cgroup2 and BPF FS, the ELF path and the program names (based on the symbol names we saw before) that we want to load.

const (

rootCgroup = "/sys/fs/cgroup/unified"

ebpfFS = "/sys/fs/bpf"

bpfCodePath = "bpf.o"

egressProgName = "egress"

ingressProgName = "ingress"

)

Let’s start running some things. First we set the rlimit to infinity. This is because eBPF maps use locked memory which has low limits by default. We don’t actually use maps yet, but we will.

func main() {

unix.Setrlimit(unix.RLIMIT_MEMLOCK, &unix.Rlimit{

Cur: unix.RLIM_INFINITY,

Max: unix.RLIM_INFINITY,

})

Then we load the binary. This first line saves us quite some work, as the library determines for us where the sections are and loads each one and its instructions separately and puts them in a nice struct for us to use later.

We also determine the paths where we will pin the different programs. That is so that they can run even after the Go program exits. Then, we can write an “unload” procedure as well which loads them from their pinned positions to unload them - otherwise we would have no way to interact with them. The BPF filesystem (mounted on /sys/fs/bpf by default) exists for this purpose - so we can pin things to it.

We also obtain a file handle to the root cgroup which we’ll use to control the entire system’s packets.

collec, err := ebpf.LoadCollection(bpfCodePath)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

var ingressProg, egressProg *ebpf.Program

ingressPinPath := filepath.Join(ebpfFS, ingressProgName)

egressPinPath := filepath.Join(ebpfFS, egressProgName)

cgroup, err := os.Open(rootCgroup)

if err != nil {

return

}

defer cgroup.Close()

Finally, we find our programs in the binary. These are called “ingress” and “egress”, as are their symbol names. We pin them to the above paths and attach them to the cgroup that we loaded. Under the hood, this calls once again the bpf syscall for each program with the command BPF_PROG_ATTACH and the types BPF_ATTACH_TYPE_CGROUP_INET_{E,IN}GRESS. It also passes the file descriptors for each BPF program that we have already loaded and for the cgroup we’re attaching to.

ingressProg = collec.Programs[ingressProgName]

ingressProg.Pin(ingressPinPath)

egressProg = collec.Programs[egressProgName]

egressProg.Pin(egressPinPath)

_, err = link.AttachCgroup(link.CgroupOptions{

Path: cgroup.Name(),

Attach: ebpf.AttachCGroupInetIngress,

Program: collec.Programs[ingressProgName],

})

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

_, err = link.AttachCgroup(link.CgroupOptions{

Path: cgroup.Name(),

Attach: ebpf.AttachCGroupInetEgress,

Program: collec.Programs[egressProgName],

})

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

}

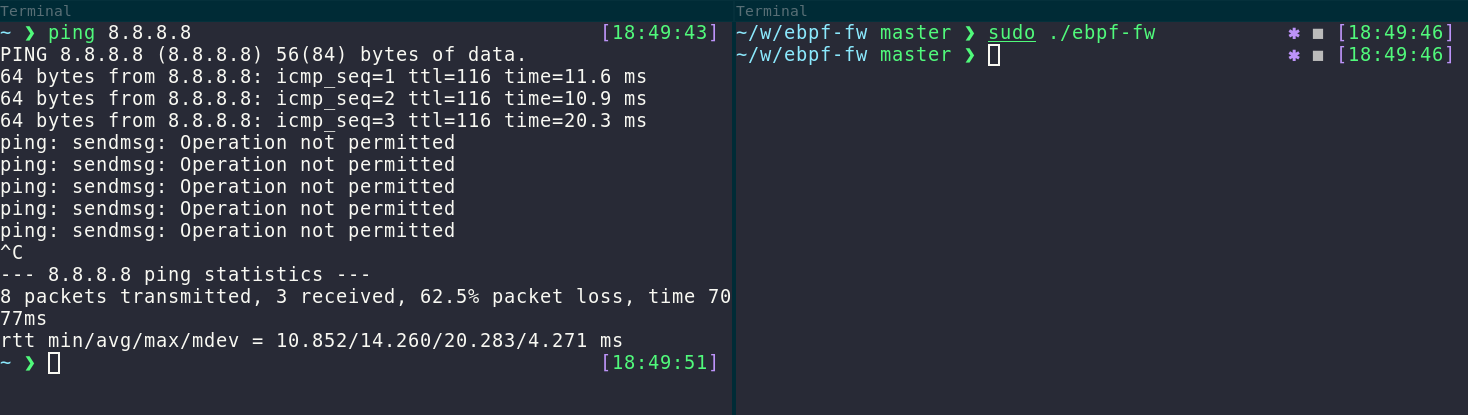

This is the end of the code! You can compile the program above with go build ./ebpf-fw.go. By running it, the BPFs will attach to the cgroup and you won’t have any connectivity. If you want to regain your internet connection, read on. :)

Thankfully, detaching the programs is a lot easier. You simply have to load the pinned programs and open the cgroup:

func main() {

var ingressProg, egressProg *ebpf.Program

ingressPinPath := filepath.Join(ebpfFS, ingressProgName)

egressPinPath := filepath.Join(ebpfFS, egressProgName)

ingressProg, err := ebpf.LoadPinnedProgram(ingressPinPath)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

egressProg, err = ebpf.LoadPinnedProgram(egressPinPath)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

cgroup, err := os.Open(rootCgroup)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

defer cgroup.Close()

and you can then detach them from the cgroup and remove the pins:

ingressProg.Detach(int(cgroup.Fd()), ebpf.AttachCGroupInetIngress, 0)

egressProg.Detach(int(cgroup.Fd()), ebpf.AttachCGroupInetEgress, 0)

os.Remove(ingressPinPath)

os.Remove(egressPinPath)

}

That was easy! There’s still more features to be added, though. We would like to control which IP addresses are blocked rather than drop all packets. This is where maps come in: We can use them to store these IP addresses and also change them on the fly via userspace, rather than have to unload and reload the programs every time.

Thankfully, using maps is also relatively easy. First we have to define our new map in the ELF file (in its own section) so that we can then load it. As we want to store simply IPv4 addresses which are just 4 bytes, an int will be enough to store them. We will use the bpf_map_def struct to define a map in the C code.

/* Map for blocking IP addresses from userspace */

struct bpf_map_def __section("maps") blocked_map = {

.type = BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH,

.key_size = sizeof(__u32),

.value_size = sizeof(__u32),

.max_entries = 10000,

};

Of course we also need to change the code to check whether either (src/dst) IP address is in the map to determine whether to block it. To do that, we need to load the packet header from kernel memory to the BPF memory, as we can’t access kernel memory directly. Then it’s simply a case of looking up that address in the map to check if it has been blocked.

/* Handle a packet: return whether it should be allowed or dropped */

inline bool handle_pkt(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

struct iphdr iph;

/* Load packet header */

bpf_skb_load_bytes(skb, 0, &iph, sizeof(struct iphdr));

/* Check if IPs are in "blocked" map */

bool blocked = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&blocked_map, &iph.saddr) || bpf_map_lookup_elem(&blocked_map, &iph.daddr);

/* Return whether it should be allowed or dropped */

return !blocked;

}

/* Ingress hook - handle incoming packets */

__section("cgroup_skb/ingress")

int ingress(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

return (int)handle_pkt(skb);

}

/* Egress hook - handle outgoing packets */

__section("cgroup_skb/egress")

int egress(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

return (int)handle_pkt(skb);

}

Now we simply have to access the map from the Go program to insert / delete entries. First, let’s declare its name in Go:

const blockedMapName = "blocked_map"

Then we also need a place to pin it so that we can load it on subsequent runs of the userspace program.

blockedPinPath := filepath.Join(ebpfFS, blockedMapName)

Upon loading the ELF file with the Cilium library, it has helpfully placed the map in its own Maps map!

blockedMap, _ = collec.Maps[blockedMapName]

blockedMap.Pin(blockedPinPath)

We can later load it again with the following code:

blockedMap, err = ebpf.LoadPinnedMap(blockedPinPath)

Finally, to insert an IP address to it, we have to first convert it from a string to an int by converting the 4 octets to little endian form, so that they appear in the same order as they do in the usual IP address format. The net and binary libraries in Go can do that for us. After converting it, we can insert it into the BPF map and the BPF program should pick it up and block it!

ip_bytes := net.ParseIP(ip_addr).To4()

ip_int := binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(ip_bytes)

if err = blockedMap.Put(&ip_int, &ip_int); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

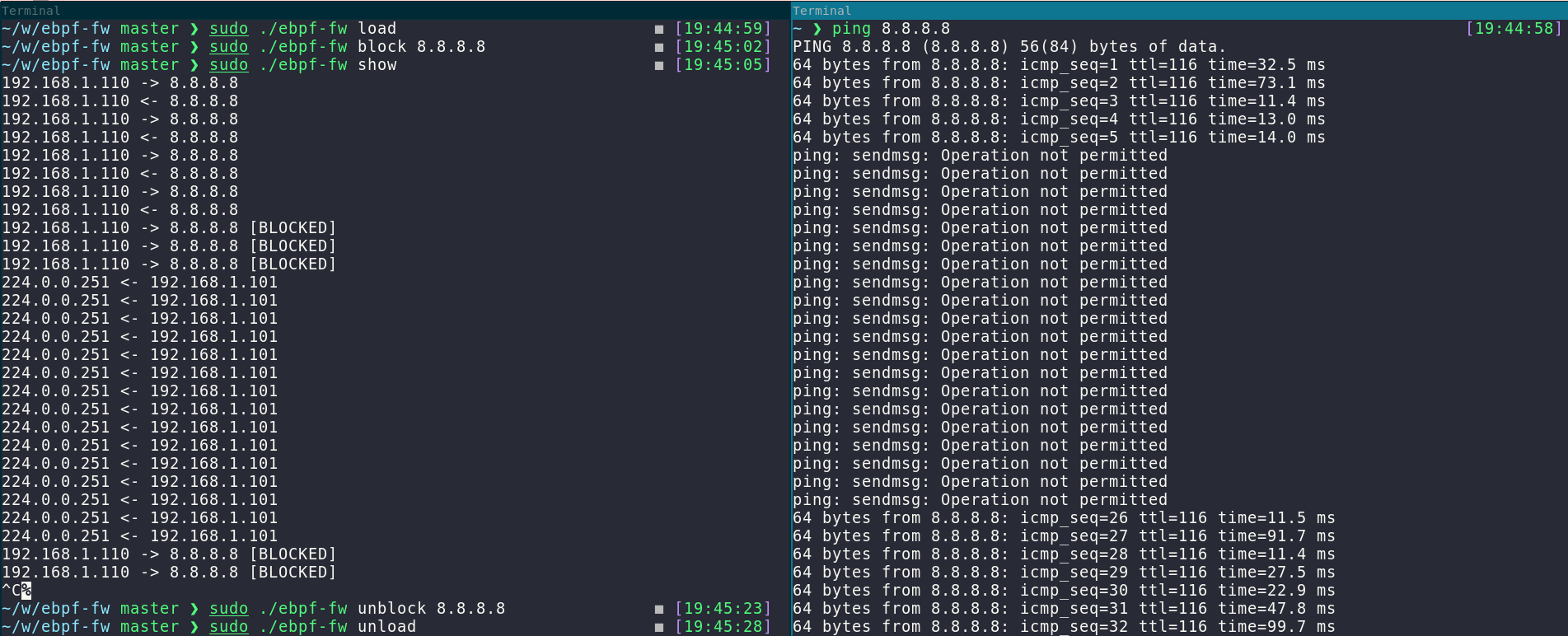

Similarly, you can add other features with maps to interact with the program via userspace. For instance, I added tracking of which IPs are seen so that I can view a list of what my computer connects to in real time. You can see my entire implementation at https://github.com/nikofil/ebpf-firewall/.

This is what it looks like when using the CLI to block an IP address while the eBPF program is loaded:

Comments