Rust-OS Kernel - Task scheduler

This post is about writing a simple, round-robin task scheduler for my Rust kernel. It builds on some concepts I wrote about in my previous post: To userspace and back!

Source code: https://github.com/nikofil/rust-os and in particular the scheduler.rs file

So, we’ve made it this far. We’ve managed to jump to userspace and have it call the kernel. That’s quite boring though! Our kernel code is still tightly coupled with the usermode program: It jumps to a specified point in the code, and is called back shortly after. That’s why we need a scheduler, so that programs can execute other programs and we have something that resembles a real kernel. Of course we have nothing to execute yet - we’d need files for that, which need a filesystem! That will come later. First, let’s make our kernel work with 2 predefined processes.

Userspace processes

First of all, let’s make our 2 processes. These should normally be stored on the filesystem, but until we have a filesystem we can just make two functions that we’ll jump to in usermode. We already have a syscall that prints its arguments to the screen.

Then we can make our process funcs. They’re going to be pretty simple: They will initialize their registers to some distinct value, so that we can see that these values stay as they are and that we don’t mess them up when switching between them. Then they will spin for a bit so that we don’t flood the console with messages, and after a bit they’ll perform a syscall. Finally, they’ll do the same thing all over again!

Simple user processes

Here are our usermode processes:

pub unsafe fn userspace_prog_1() {

asm!("\

mov rbx, 0xf0000000

prog1start:

push 0x595ca11a // keep the syscall number in the stack

mov rbp, 0x0 // distinct values for each register

mov rax, 0x1

mov rcx, 0x3

mov rdx, 0x4

mov rdi, 0x6

mov r8, 0x7

mov r9, 0x8

mov r10, 0x9

mov r11, 0x10

mov r12, 0x11

mov r13, 0x12

mov r14, 0x13

mov r15, 0x14

xor rax, rax

prog1loop:

inc rax

cmp rax, 0x4000000

jnz prog1loop // loop for some milliseconds

pop rax // pop syscall number from the stack

inc rbx // increase loop counter

mov rdi, rsp // first syscall arg is rsp

mov rsi, rbx // second syscall arg is the loop counter

syscall // perform the syscall!

jmp prog1start // do it all over

":::: "volatile", "intel");

}

pub unsafe fn userspace_prog_2() {

asm!("\

mov rbx, 0

prog2start:

push 0x595ca11b // keep the syscall number in the stack

mov rbp, 0x100 // distinct values for each register

mov rax, 0x101

mov rcx, 0x103

mov rdx, 0x104

mov rdi, 0x106

mov r8, 0x107

mov r9, 0x108

mov r10, 0x109

mov r11, 0x110

mov r12, 0x111

mov r13, 0x112

mov r14, 0x113

mov r15, 0x114

xor rax, rax

prog2loop:

inc rax

cmp rax, 0x4000000

jnz prog2loop // loop for some milliseconds

pop rax // pop syscall number from the stack

inc rbx // increase loop counter

mov rdi, rsp // first syscall arg is rsp

mov rsi, rbx // second syscall arg is the loop counter

syscall // perform the syscall!

jmp prog2start // do it all over

":::: "volatile", "intel");

}

Pretty straightforward - they’re almost identical except for the different numbers. We also give the syscall rsp and rbx as parameters, so that they get printed to the screen.

Executing a user process

We can’t multi-task yet but, since the previous post, we can jump to usermode and see what the output of only one of these looks like. We first re-define the code that sets up the page table, enables it and jumps to it as a function.

pub unsafe fn exec(fn_addr: mem::VirtAddr) {

let userspace_fn_phys = fn_addr.to_phys().unwrap().0; // virtual address to physical

let page_phys_start = (userspace_fn_phys.addr() >> 12) << 12; // zero out page offset to get which page we should map

let fn_page_offset = userspace_fn_phys.addr() - page_phys_start; // offset of function from page start

let userspace_fn_virt_base = 0x400000; // target virtual address of page

let userspace_fn_virt = userspace_fn_virt_base + fn_page_offset; // target virtual address of function

serial_println!("Mapping {:x} to {:x}", page_phys_start, userspace_fn_virt_base);

let mut task_pt = mem::PageTable::new(); // copy over the kernel's page tables

task_pt.map_virt_to_phys(

mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace_fn_virt_base),

mem::PhysAddr::new(page_phys_start),

mem::BIT_PRESENT | mem::BIT_USER); // map the program's code

task_pt.map_virt_to_phys(

mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace_fn_virt_base).offset(0x1000),

mem::PhysAddr::new(page_phys_start).offset(0x1000),

mem::BIT_PRESENT | mem::BIT_USER); // also map another page to be sure we got the entire function in

let mut stack_space: Vec<u8> = Vec::with_capacity(0x1000); // allocate some memory to use for the stack

let stack_space_phys = mem::VirtAddr::new(stack_space.as_mut_ptr() as *const u8 as u64).to_phys().unwrap().0;

// take physical address of stack

task_pt.map_virt_to_phys(

mem::VirtAddr::new(0x800000),

stack_space_phys,

mem::BIT_PRESENT | mem::BIT_WRITABLE | mem::BIT_USER); // map the stack memory to 0x800000

task_pt.enable(); // enable page table

jmp_to_usermode(mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace_fn_virt),

mem::VirtAddr::new(0x801000)); // jump to start of function

drop(stack_space); // make sure the stack space doesn't get free'd earlier, as the process needs it to run

}

Calling it then is simply:

let userspace_fn_1_in_kernel = mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace::userspace_prog_1 as *const () as u64);

unsafe {

scheduler::exec(userspace_fn_1_in_kernel);

}

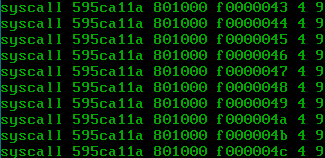

We’re now getting some result on the console, as we expected. I changed the syscall code to print the arguments in hexadecimal here, so that we can better see that their values match with the counter and the user program’s stack pointer.

This is what we expected to see:

raxis the syscall number0x595ca11a- The first parameter, in

rdi, isrspwhich matches the starting stack pointer (0x801000) - The second parameter, stored in

rsi, is the counter of how many times we called the syscall (starting with0xf0000000as defined above) - The third parameter is stored in

rdx(as we follow the Linux convention for syscalls), which happens to be4 - Similarly the fourth parameter is stored in

r10, which happens to be9

All in all, the results are good! Let’s move on to defining our processes, so that we can move between them.

Building a Task struct

The task context

What is a process? How can we take the processor from executing one process to another, and then back, while giving the processes the illusion they haven’t been interrupted at all?

The most important pieces of information that we need to keep about the state of a process at any given time are its registers and memory. Other things might be needed in the future, such as a mapping of file handles in the program to actual files in the filesystem, but we don’t even have a filesystem yet!

When we want to swap out the currently executing program and swap in the next one to be executed, the first thing we must do is save the previously executing program’s registers. That’s because we want to be able to use the registers in our kernel without losing the values the program has stored in them. Otherwise the program could never work if, at any moment, it could be interrupted and its registers changed. The set of all registers that we want to save is called the task context and will be the first struct that we have to define, with a field for each register:

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct Context {

pub rbp: u64,

pub rax: u64,

pub rbx: u64,

pub rcx: u64,

pub rdx: u64,

pub rsi: u64,

pub rdi: u64,

pub r8: u64,

pub r9: u64,

pub r10: u64,

pub r11: u64,

pub r12: u64,

pub r13: u64,

pub r14: u64,

pub r15: u64,

pub rip: u64,

pub cs: u64,

pub rflags: u64,

pub rsp: u64,

pub ss: u64,

}

This particular order of the registers in the struct (particularly the last few) will be important soon.

Upon taking back control from an executing program, saving its context is the first thing we need to do.

Other info to save

Of course, we can’t have programs reading each other’s memory! Virtual memory is also a part of the context, however we don’t need to save anything each time we switch contexts. Why is that? Well, because the virtual memory of a process is defined by the page table that is assigned to that process - this way we can tell apart the memory of multiple processes while they might all see the same virtual addresses. We only define the page table once, when starting the process. Then we hand that process the keys and let it do what it wishes with its virtual memory, and the processor chugs along and translates the virtual addresses to physical. Therefore we don’t need to save anything when switching contexts: We know the address of the page table of each process and we just need to restore that address to the appropriate register (cr3) when switching.

Besides these things, a process needs a stack to run. That’s where local variables, function parameters and return values are stored. The stack gets no special treatement from the processor: the kernel is responsible for making some room for it in the memory and passing the pointer to the program in the rsp register. How do we make that room in the memory? Well, we just allocate an array of bytes! And what is an array of bytes in Rust? Simply a Vec<u8>.

We have to keep that Vec somewhere, however. We don’t want Rust to consider it unused and reclaim the memory before the process is done with it. What better place to keep it than our upcoming Task struct, then?

You might notice a disrepancy: We didn’t need to allocate any other memory for the program. At this point the program memory (besides the stack) only contains the program code - but where does that memory come from?

The answer is that we’re cheating a bit here: At this point all our userspace program code is simply functions in our kernel. We take their physical address, map it to a virtual address like 0x400000, jump to it while in ring 3 and call it a day. The compiler makes sure these functions are somewhere in the memory, and it doesn’t let anyone mess with that piece of memory. So we don’t need to explicitly allocate any memory for the code. We will have to, however, once we want to load arbitrary programs from a filesystem.

But anyway, back to the stack. The stack grows downwards: if you keep pushing variables to it, the rsp register which points to the last element in the stack will decrease. Therefore, the initial value of rsp will be a pointer to the first byte after the stack space. This is essentially the virtual address to which we mapped the stack, plus the size of the stack.

Finally, the program needs to start somewhere. This also depends on what virtual address we map it to. Because we can only map pages and the function is not guaranteed to start on the beginning of a page, the program might not start at the address we map its page to but some bytes later. This is another address that we need to keep so that we can set rip (the instruction pointer) to it when first starting the program.

For the last two, I use an enum called TaskState for storing these virtual addresses (rip and rsp) or storing the full Context of an already started program. That’s because, before starting the program, we don’t need the full context: We start it with a default one. We only need to keep these two virtual addresses so that we know where to start it. Afterwards, these addresses are no longer needed. Instead we only need the Context that we saved when we last suspended the program.

The final Task struct

Having said all that, in all its glory, here is our Task struct!

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

enum TaskState { // a task's state can either be

SavedContext(Context), // a saved context

StartingInfo(mem::VirtAddr, mem::VirtAddr), // or a starting instruction and stack pointer

}

struct Task {

state: TaskState, // the current state of the task

task_pt: Box<mem::PageTable>, // the page table for this task

_stack_vec: Vec<u8>, // a vector to keep the task's stack space

}

impl Task {

pub fn new(

exec_base: mem::VirtAddr,

stack_end: mem::VirtAddr,

_stack_vec: Vec<u8>,

task_pt: Box<mem::PageTable>,

) -> Task {

Task {

state: TaskState::StartingInfo(exec_base, stack_end),

_stack_vec,

task_pt,

}

}

}

impl Display for Task {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut core::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> core::fmt::Result {

unsafe {

write!(f, "PT: {}, Context: {:x?}", self.task_pt.phys_addr(), self.state)

}

}

}

Simple, huh? We have the right structure, but it’s still missing all its functionality.

Interrupting the running process

We’re very close, now. We have the structures needed to define a process, we just need to be able to save and restore a context which requires some assembly in order to make sure that Rust doesn’t mess with the registers of the process before we can save them. Afterwards things are quite straightforward.

Timer interrupt

In order to get control back from the running program, we’re going to use the timer interrupt caused by the Programmable Interval Timer. Another option is to use the newer APIC timer but I will use the former, as I’ve already set it up following https://os.phil-opp.com/hardware-interrupts/.

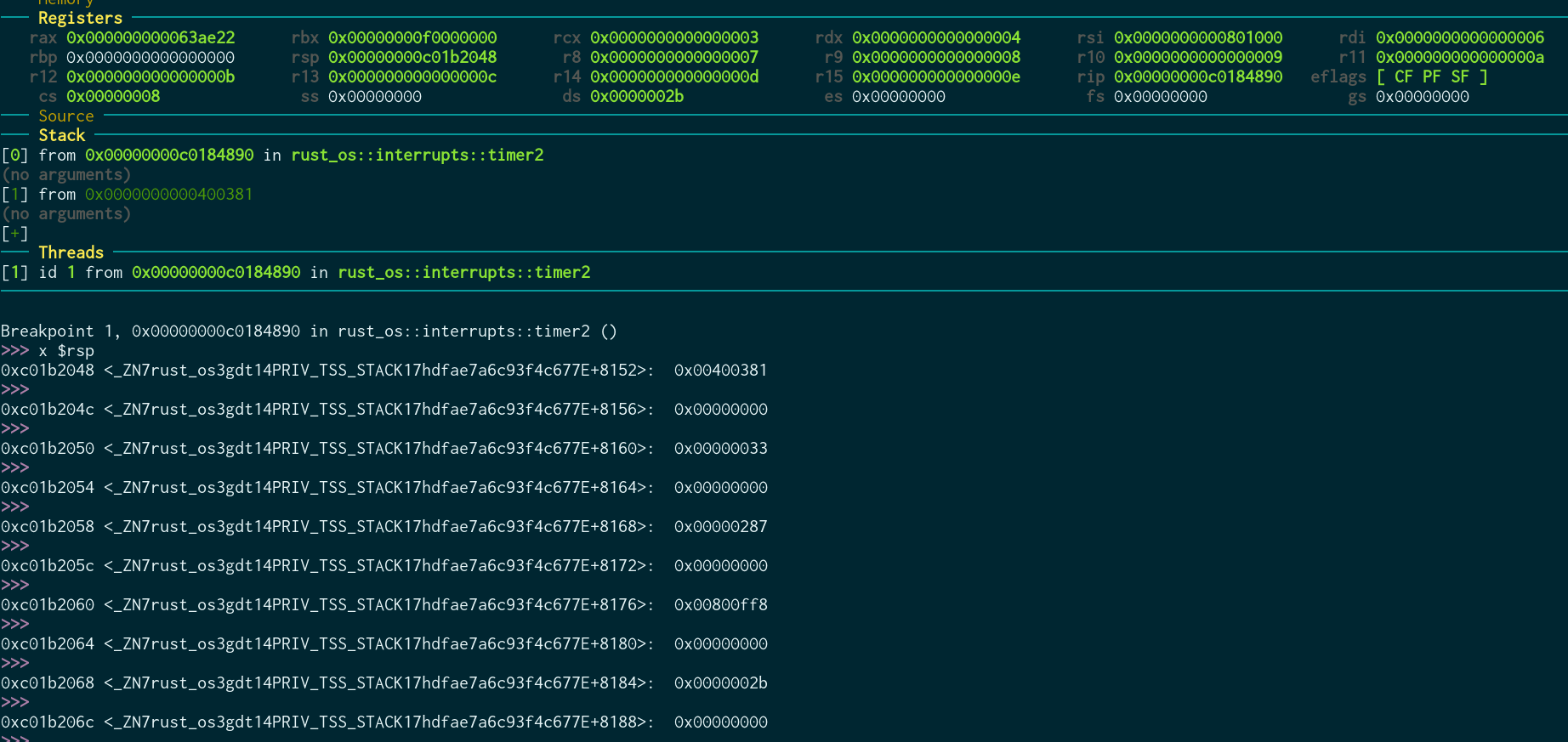

To reiterate, typically hardware interrupt 32 is used for the PIT. To start with, let’s see what state the processor is in right after performing a timer interrupt. I changed my timer handler function to only contain a nop and set a breakpoint on it in GDB. This is the state of the processor at that point:

Almost all of the registers have the same values as they did in a moment before, except for a few very important ones:

rippoints to the interrupt handler, instead of the user programrsppoints to a new stackcshas changed so that our CPL is 3 (we are in kernel mode)- Interrupts have been disabled, as the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) entry for the timer interrupt states that they should be

We’ll have to restore these things after handling this interrupt. In this case (timer interrupt) we won’t restore them now, though. Instead we’ll store them in a Context, which we’ll use at a later time when we want to give control back to this program. To do that, the processor has pushed the old values of all the registers that it changed to our stack! This is what the stack in the above image contains:

| rsp offset | saved register |

|---|---|

| +0 | rip |

| +8 | cs |

| +16 | rflags |

| +24 | rsp |

| +32 | ss |

(Note that each one is 8 bytes long, so two rows in the image above)

How did the processor find its new rip, rsp and cs? Through the IDT and GDT! The IDT contains the address of the handler for each interrupt, which the processor jumps to. It also contains what the new code segment should be. rsp is slightly different: it depends on the GDT’s privilege stack table: When an interrupt causes the processor to change to CPL #n, then the n-th entry in the privilege stack table is used to determine the new rsp. This means the first (index 0) entry is used in our case. For me the following vector holds the stack used:

pub static mut PRIV_TSS_STACK: [u8; STACK_SIZE] = [0; STACK_SIZE];

GDB helpfully tells us the offset for each entry in the stack! As my stack is 8192 bytes large, you can see the very first thing to be pushed (the ss register) is right at the end of this stack.

Saving the context

We now know what we have to do: We need to save every register in the Context struct before it has a chance to change! The CPU already saved some important ones for us, now we need to save the rest. As rsp is saved for us and we have a new stack to use, we can save these registers in the stack, in the opposite order from which they appear in Context. rip, cs, rflags, rsp and ss are already there so we just need to save the rest.

Afterwards, what rsp points to is exactly the struct that our Context struct describes! All the registers are in the right place. Therefore, we can get its value and use it as a *const Context to save in our Task struct. Then we subtract some space from rsp to give the timer handler some space for local variables, as to not overwrite what we just created.

#[naked]

#[inline(always)]

pub unsafe fn get_context() -> *const Context {

let ctxp: *const Context;

asm!("push r15; push r14; push r13; push r12; push r11; push r10; push r9;\

push r8; push rdi; push rsi; push rdx; push rcx; push rbx; push rax; push rbp;\

mov $0, rsp; sub rsp, 0x400;"

: "=r"(ctxp) ::: "intel", "volatile");

ctxp

}

Restoring the context

Restoring the context is then simply a matter of moving rsp to the Context pointer and doing the exact opposite process from what we did above. We pop all of the registers that we pushed above and, finally, use the iretq instruction to restore the 5 registers that the processor saved. That is what the instruction was named after: returning from an interrupt, as its functionality in this case is the inverse of what the processor does on an interrupt.

#[naked]

#[inline(always)]

pub unsafe fn restore_context(ctxr: &Context) {

asm!("mov rsp, $0;\

pop rbp; pop rax; pop rbx; pop rcx; pop rdx; pop rsi; pop rdi; pop r8; pop r9;\

pop r10; pop r11; pop r12; pop r13; pop r14; pop r15; iretq;"

:: "r"(ctxr) :: "intel", "volatile");

}

Testing the procedure

We should now hopefully be able to save and restore the Context of a process. We already have the timer interrupting the process every few milliseconds, so let’s try to save and restore its context. To have a visual confirmation that something happened, I’m also incrementing the value of rdx which gets printed when we perform a syscall.

#[naked]

unsafe extern fn timer2(stack_frame: &mut InterruptStackFrame) {

let ctx = get_context(); // get current context

unsafe { (ctx as *mut Context).as_mut().unwrap().rdx += 1; } // increment rdx

end_of_interrupt(32); // mark timer interrupt as finished so that PIT can interrupt again

restore_context(&*ctx); // restore current context

}

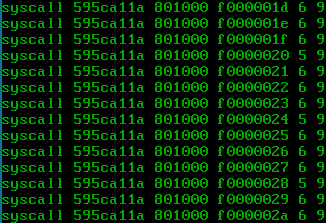

Let’s see if we can see rdx incrementing:

Yup, we can see rdx take values between 5 and 6. What does this mean?

Since we reset the value of rdx to 4 after each syscall and then we wait for a few ms before performing the next syscall, it means that while we wait the PIT triggers once or twice, causing rdx to increment by that amount. So, our context saving and restoring seems to work with one process! Let’s now try with two.

Scheduling processes

The difficult part is now over. We have all the building blocks to build a simple scheduler without the need to delve into the processor’s internals anymore.

Our scheduler will be fairly simple. We only need a list of the running Tasks and the index of the one running currently, so that we know which one is next. On each timer interrupt we proceed in a round-robin fashion, saving the current context and restoring the next (or in the case a task has not yet started, initalizing it with the given addresses).

We need to have a single static scheduler to keep all this info, for which we’ll use the lazy_static crate. We’ll keep the members of Scheduler behind mutexes so that Rust doesn’t complain about them possibly being accessible from multiple threads. Also, the previously used exec function is a pretty useful method to have in Scheduler. We’ll move it there (renamed to schedule), altering it to only create the page table and not enable it immediately, and saving all the information needed to start the task in a new Task struct.

All in all, here is the code for the Scheduler. It should be simple to understand:

pub struct Scheduler {

tasks: Mutex<Vec<Task>>,

cur_task: Mutex<Option<usize>>,

}

impl Scheduler {

pub fn new() -> Scheduler {

Scheduler {

tasks: Mutex::new(Vec::new()),

cur_task: Mutex::new(None), // so that next task is 0

}

}

pub unsafe fn schedule(&self, fn_addr: mem::VirtAddr) {

let userspace_fn_phys = fn_addr.to_phys().unwrap().0; // virtual address to physical

let page_phys_start = (userspace_fn_phys.addr() >> 12) << 12; // zero out page offset to get which page we should map

let fn_page_offset = userspace_fn_phys.addr() - page_phys_start; // offset of function from page start

let userspace_fn_virt_base = 0x400000; // target virtual address of page

let userspace_fn_virt = userspace_fn_virt_base + fn_page_offset; // target virtual address of function

serial_println!("Mapping {:x} to {:x}", page_phys_start, userspace_fn_virt_base);

let mut task_pt = mem::PageTable::new(); // copy over the kernel's page tables

task_pt.map_virt_to_phys(

mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace_fn_virt_base),

mem::PhysAddr::new(page_phys_start),

mem::BIT_PRESENT | mem::BIT_USER); // map the program's code

task_pt.map_virt_to_phys(

mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace_fn_virt_base).offset(0x1000),

mem::PhysAddr::new(page_phys_start).offset(0x1000),

mem::BIT_PRESENT | mem::BIT_USER); // also map another page to be sure we got the entire function in

let mut stack_space: Vec<u8> = Vec::with_capacity(0x1000); // allocate some memory to use for the stack

let stack_space_phys = mem::VirtAddr::new(stack_space.as_mut_ptr() as *const u8 as u64).to_phys().unwrap().0;

// take physical address of stack

task_pt.map_virt_to_phys(

mem::VirtAddr::new(0x800000),

stack_space_phys,

mem::BIT_PRESENT | mem::BIT_WRITABLE | mem::BIT_USER); // map the stack memory to 0x800000

let task = Task::new(mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace_fn_virt),

mem::VirtAddr::new(0x801000), stack_space, task_pt); // create task struct

self.tasks.lock().push(task); // push task struct to list of tasks

}

pub unsafe fn save_current_context(&self, ctxp: *const Context) {

self.cur_task.lock().map(|cur_task_idx| { // if there is a current task

let ctx = (*ctxp).clone();

self.tasks.lock()[cur_task_idx].state = TaskState::SavedContext(ctx); // replace its context with the given one

});

}

pub unsafe fn run_next(&self) {

let tasks_len = self.tasks.lock().len(); // how many tasks are available

if tasks_len > 0 {

let task_state = {

let mut cur_task_opt = self.cur_task.lock(); // lock the current task index

let cur_task = cur_task_opt.get_or_insert(0); // default to 0

let next_task = (*cur_task + 1) % tasks_len; // next task index

*cur_task = next_task;

let task = &self.tasks.lock()[next_task]; // get the next task

serial_println!("Switching to task #{} ({})", next_task, task);

task.task_pt.enable(); // enable task's page table

task.state.clone() // clone task state information

}; // release held locks

match task_state {

TaskState::SavedContext(ctx) => {

restore_context(&ctx) // either restore the saved context

},

TaskState::StartingInfo(exec_base, stack_end) => {

jmp_to_usermode(exec_base, stack_end) // or initialize the task with the given instruction, stack pointers

},

}

}

}

}

lazy_static! {

pub static ref SCHEDULER: Scheduler = Scheduler::new();

}

We can also alter the timer now to do its intended job, that is to save the current Context and restore the next one. We’ve already made the methods necessary for that, so it’s simply a matter of calling the scheduler.

#[naked]

unsafe extern fn timer(_stack_frame: &mut InterruptStackFrame) {

let ctx = scheduler::get_context();

scheduler::SCHEDULER.save_current_context(ctx);

end_of_interrupt(32);

scheduler::SCHEDULER.run_next();

}

Finally, we can schedule the two usermode programs we created in the start of this post and then start executing them. They should finally be able to run together!

let userspace_fn_1_in_kernel = mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace::userspace_prog_1 as *const () as u64);

let userspace_fn_2_in_kernel = mem::VirtAddr::new(userspace::userspace_prog_2 as *const () as u64);

unsafe {

let sched = &scheduler::SCHEDULER;

sched.schedule(userspace_fn_1_in_kernel);

sched.schedule(userspace_fn_2_in_kernel); // schedule the two methods

loop {

sched.run_next(); // run the next task, forever

}

}

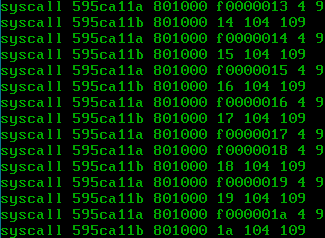

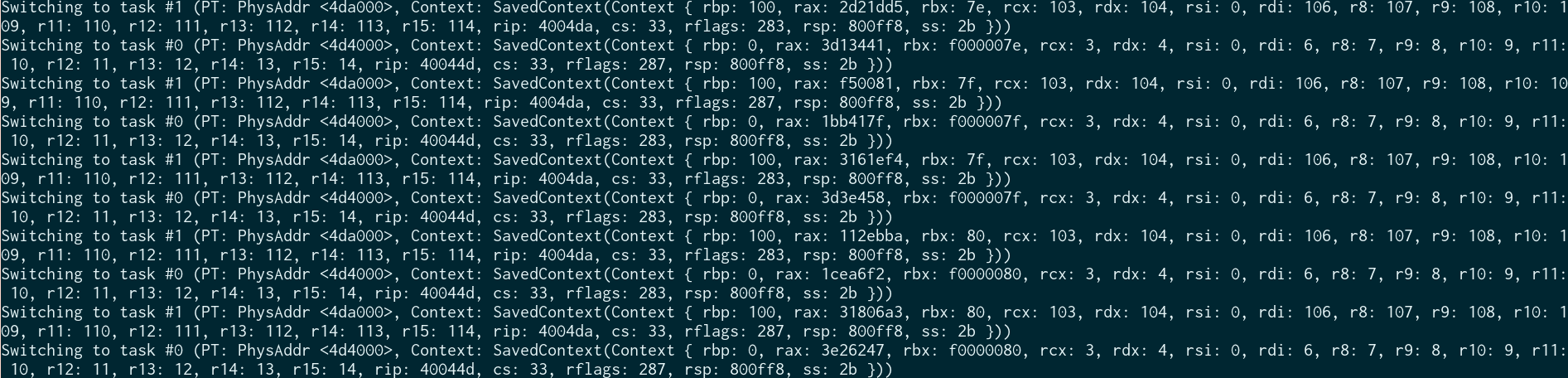

We can see the CPU alternating between the two programs, while maintaining their state:

We can also see the output in the serial console! There, it’s clear that all the registers are properly saved and restored:

This complicated part of the kernel is finally done (until some bugs arise, at least). A nice task to follow up with would be to implement a FAT16 driver so that we finally have a file system, and making the appropriate syscalls so we can execute a binary that lives there.

Comments